The Structural Dynamics of U.S. Monetary Expansion in the Post-Bretton Woods Regime

The long-run trajectory of the U.S. monetary base exhibits a pattern that is best characterized not as a sequence of temporary policy deviations, but as a persistent structural feature of the fiat‐based monetary architecture established after 1971. Prior to the dissolution of the Bretton Woods system, external convertibility requirements imposed an exogenous constraint on the rate of dollar creation. The suspension of gold convertibility fundamentally altered this institutional framework, removing the binding constraint that had previously anchored monetary expansion to the dynamics of gold reserves and external balance considerations. Following this transition, U.S. monetary growth became determined primarily by domestic fiscal imperatives, liquidity conditions, and macroeconomic stabilization objectives rather than by external discipline.

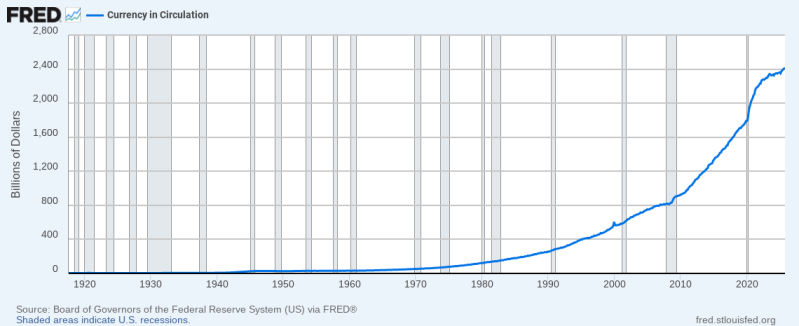

Historical data confirm the durability of this regime shift. The U.S. monetary base increased from approximately $140 billion in 1960 to $200 billion in 1970, and then to roughly $385 billion by 1980—reflecting a near-doubling during a decade characterized by the absence of external constraints on issuance. Over subsequent decades, the magnitude and frequency of monetary expansion intensified. The contemporary monetary base exceeds $2 trillion, representing more than a twenty-fold increase relative to its pre-1971 level. This escalation cannot be adequately attributed to cyclical factors alone; it reflects a complex interaction between structurally elevated federal deficits, compounding public debt dynamics, systemic geopolitical uncertainty, and the growing dependence of fiscal authorities on central bank balance-sheet capacity to sustain government financing and stabilize financial conditions during shocks.

These dynamics carry significant implications for domestic purchasing power. A persistent divergence between monetary expansion and real economic output induces a continuous erosion in the real value of nominal balances—an implicit form of taxation that operates through currency dilution rather than explicit fiscal measures. The intergenerational multiplication of the monetary base underscores the structural nature of this erosion: a twenty-fold increase within two generations is unlikely to represent an upper bound under the prevailing institutional configuration. For households, the relevant risk is therefore not hypothetical but intrinsic to the long-run behavior of unconstrained fiat issuance.

Historically, periods marked by sustained monetary dilution have elevated the relevance of asset classes anchored in credible scarcity. Under commodity-based systems, gold served this function due to its non-discretionary supply profile. In the contemporary environment, certain digital assets replicate this scarcity property through rule-based issuance mechanisms encoded at the protocol level. However, many existing cryptocurrencies are handicapped by extremely limited supply scales, which induce volatility, constrain adoption, and limit their utility as credible monetary substitutes.

A USD-scale, hard-capped digital asset such as HedgeDollar represents a distinct departure from these limitations. By operating at real-world monetary scale while remaining insulated from discretionary expansion, it offers a scarcity-anchored alternative that is compatible with high-volume economic activity. Its rule-based architecture is designed to maintain purchasing-power stability in an environment where fiat issuance is structurally predisposed toward acceleration. In this sense, HedgeDollar can be understood as a contemporary analogue to historical scarcity assets—adapted to the institutional, technological, and monetary realities of the post-Bretton Woods era.